Choosing a Data Structure

A few years ago my friend Arnold told me that whenever he learns a new programming language, he writes code in that language to solve the same specific problem. Sort of like an extended Hello World. That problem can be stated as follows:

Write a program to generate and print a maze, where each room is connected to every other without cycles.

This problem is a nice one to explore a few programming topics and opens the door for expansion into other interesting ones. In this article I am going to discuss choosing a data structure to represent a maze as needed for the basic problem as stated.

Requirements and Vocabulary

Mazes can be made in a variety of shapes and styles. For this exercise, we will only be discussing two dimensional, rectangular, simply-connected mazes of arbitrary size. There will be no closed-off areas and no path cycles. We will call the rooms of the maze “cells”. We will label the cells starting from 0 and increasing from left to right across the first row, then continuing with the next row.

Two adjacent cells may or may not have a wall between them. If there is no wall, then we say that there is a passage between them. Start and end points are not relevant to the creation of the maze layout and can be any two cells chosen later. We use “north” to refer a cell “above” another cell, “east” to refer to a cell to the right, “south” for down, and “west” for left.

Uses for the Data Structure

When choosing a data structure it can be useful to list the things you expect it to do. At this point, we don’t know many details about how we will do things. But for now we know we want to:

-

Generate a valid maze. There will be multiple ways to generate mazes with different characteristics.

-

Print the layout of the maze to the console. This will probably involve visiting each cell and determining if it is connected to its neighbors with passages or blocked with walls.

Later we will want to:

- Solve the maze. This will probably involve determining if two arbitrary nodes are connected. But since this isn’t a requirement yet, we won’t add functions for this now. YAGNI.

Ad Hoc

The first data structure that comes to mind is an array of cells, where each cell contains bits to track each of connections to the north, east, south, and west. This works. It is space efficient and discovering if the connection between two cells is a passage or a wall is determined by simply indexing the array and looking at the properties of one of the two cells. When generating the maze, you must take care that the connections between adjacent cells remain in sync. That is, if cell t says there is a passage to cell u, then cell u must say that there is a passage to cell t. This data structure is redundant in that the connection between two adjacent cells is tracked by both cells. And it feels awkward.

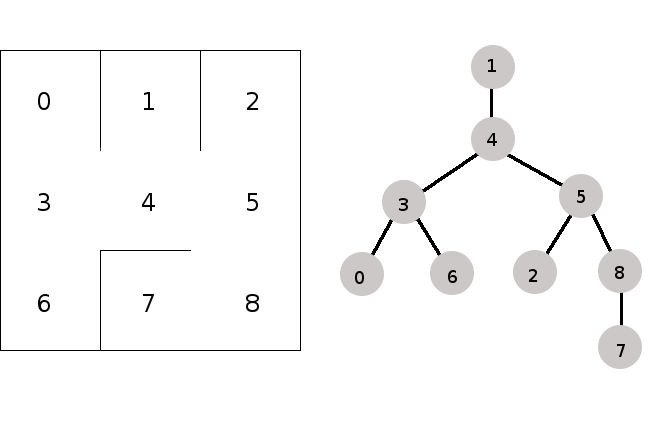

A Graph

The mazes we are discussing may be thought of as undirected acyclic graphs. The cells are nodes and the passages between cells are the edges. Any cell may be chosen as the root and the nodes can be labeled with the cell number.

Does this help us? Let’s see. A graph is often represented using an adjacency list or an adjacency matrix.

Adjacency List

In an adjacency list, each node carries a list of those nodes it is connected to. So the main part of our data structure would be a vector of nodes, where each node contains a vector of neighboring nodes. The vector of neighbors will be small: a node can be connected to one, two, or three others. Determining if two nodes t and u are connected requires indexing the vector of nodes to find node t, and then searching its small vector of neighbors for node u. Finding a node’s connected neighbors requires indexing the vector of nodes to find the node then walking the small vector of neighbors. This is not too complicated.

If two nodes are connected, each will point to the other. While redundant in that way, this is still a relatively efficient data structure. It could work, but it feels more complicated than the “Ad Hoc” version. Let’s keep exploring.

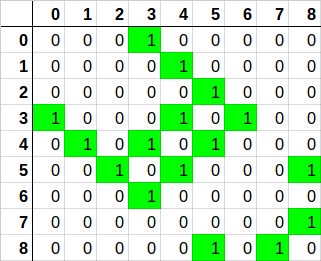

Adjacency Matrix

For a maze with n number of nodes, picture a matrix labeled 0-(n-1) across the top and 0-(n-1) down the left size. For each position x,y in the matrix, the table will contain a 1 if nodes x and y are connected or a 0 if nodes x and y are not connected.

Determining if two nodes are connected is indexing a single position in the matrix to see if it is a 1. Finding a node’s neighbors is walking that node’s row looking for ones. Again, this is not too complicated.

The matrix holds zeros and ones, so we only need one bit for each position. However, we need n² bits. This will be a very sparse matrix because each node can only have four possible neighbors. This is an inefficient use of space. It might be fine for the typical mazes we expect a human to solve, but let’s assume we must support Mazes of Unusual Size. We can do better.

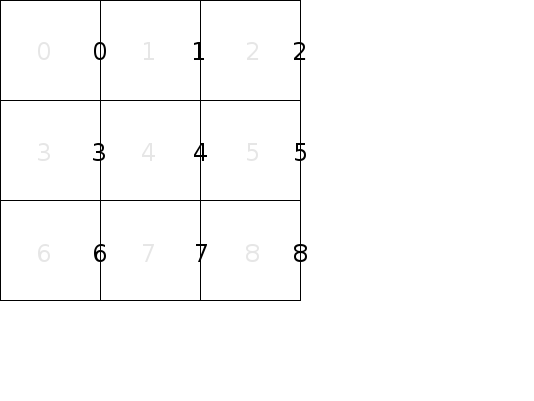

Vector of Edges

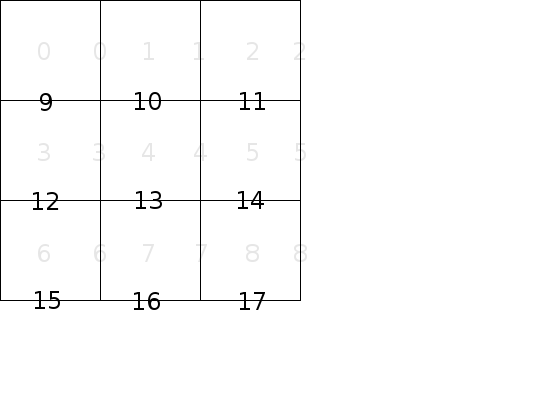

For a maze with n nodes, let’s label the vertical walls of the maze from 0 to n-1, as shown here:

And let’s label the horizontal walls in the same fashion, but starting with n instead of 0, as shown here:

Note that we are interested in the walls between two cells, so we don’t care about the walls that surround the maze. We include the walls at the right and bottom edges of the maze in our numbering because it makes finding the wall between a given set of cells easy. We never actually use those values.

To represent the walls, we only need a vector of bits walls where 0 represents a passage between two cells and 1 represents a wall.

If cells t and u are adjacent in the same row, then to find out if there is a wall or a passage between them, index the walls vector with the cell number of the cell with the lower index.

For example, to see if there is a passage between cell 1 and cell 2, look at the value of walls[1].

A 1 means there is a wall and a 0 means there is a passage.

If cells v and w are adjacent in the same column, then to find out if there is a wall or passage between them, index the walls vector with n plus the cell number of cell with the lower index.

For example, to see if there is a passage between cell 2 and 5, look at the value of walls[n + 2].

As a variation, we could keep two vectors: one for the horizontal walls and one for the vertical walls. This allows for slightly faster lookup for the horizontal walls because you don’t need to perform an addition. However, in practice it is convenient for the entire wall configuration to be contained in a single vector.

Of the options considered, I like this “Vector of Edges” representation best because it is efficient, easy to understand, and simple to code.

Sample Implementation of “Vector of Edges”

Here is a sample implementation of the “Vector of Edges” design in C++. I have omitted the details of creating the wall configuration and printing the maze. We can visit those template function implementations later, but if you want to see the source code for those right now, you can visit https://github.com/smeredith/maze/tree/choosing-a-datastructure.

I recognize that the std::vector<bool> specialization has some peculiarities, but for our purposes it is fine.

I considered std::bitset but I want to configure the size of mazes at runtime.

#pragma once

#include <vector>

// This class represents a rectangular maze of a given width and height. A maze

// is made up of cells. Adjacent cells either have a wall between them or not.

// If not, then the adjacent calls are part of the same path.

//

// Cells are numbered from left to right as 0 - (n-1) where n is the total

// number of cells in the maze.

//

// A Maze instance is immutable.

class Maze

{

public:

// Pass in a function used to generate the wall configuration.

template<typename Func>

Maze(std::size_t width, std::size_t height, Func generateWalls) :

width(width),

height(height),

numCells(width*height),

walls(generateWalls(*this))

{

}

// The number of cells in this maze.

std::size_t size() const

{

return numCells;

}

// Get the neighbor to the east of the given cell.

std::size_t neighborToTheEast(std::size_t cell) const

{

return cell + 1;

}

// Get the neighbor to the south of the given cell.

std::size_t neighborToTheSouth(std::size_t cell) const

{

return cell + width;

}

// True if the given cell is in the last row of the maze.

bool lastRow(std::size_t cell) const

{

return (cell >= (numCells - width));

}

// True if the given cell is in the last column of the maze.

bool lastCol(std::size_t cell) const

{

return ((cell+1) % width) == 0;

}

// Call a function for every cell in the maze. This is useful for

// printing the maze to the console.

template<typename Func>

void traverse(Func callback) const

{

for(std::size_t i = 0; i < numCells; i++)

{

callback(walls[i], walls[numCells + i], lastCol(i), lastRow(i));

}

}

private:

std::size_t width;

std::size_t height;

std::size_t numCells;

// The walls of the maze are represented as vector of bools, where the

// wall to the east of cell n is wall n, and the wall to the south of

// cell n is wall numCells + n. True means there is a wall between two

// cells. False means there is a passage between two cells.

// Initialized in the ctor.

std::vector<bool> walls;

};

Notice that the entire state of a maze is width, height, and a vector of bits describing its walls.

(The data member numCells is an optimization to reduce the number of width * height calculations to one.)

The member functions provided are limited to what I needed to generate the maze and to implement traverse() to print it.

Conclusion

We looked a four possible data structures to use for the representation of a maze. We did a casual analysis of each. Of those considered, I like the “Vector of Edges” because it is simple and efficient. In the http://www.bitmine.org/init-immutable/, I discuss why I am passing an initialization function in to the constructor.