A Strategy for Initializing Immutable Objects

In my last article, Choosing a Data Structure, I created an immutable class. I stated that client code must be able to initialize instances of this class. That initialization is harder than passing in a few variables–some non-trivial logic is involved. In this article we will discuss several ways to approach initialization, with one being better than the rest. A design emerges as it might in real life.

Class Maze

Recall that the class under discussion is Maze: a class with the single responsibility of storing the configuration of a maze.

Our current requirements are 1) to create maze wall configuration using different algorithms, and 2) to print the maze to the console.

We know that we will have a future requirement to solve a maze.

Why Immutable?

I am following a design principle that says classes should be immutable unless there is a good reason for them not to be. This is a common theme in Java and functional programming, but less common in C++. The details of why this is a good idea are covered elsewhere, but I will mention thread safety as a huge advantage to immutable objects.

Is there a good reason for the Maze class to be mutable?

Perhaps you would like your maze creation algorithm to start with an uninitialized maze and add walls until it is complete.

That seems reasonable, but I’ll show that we can do it another way with an immutable Maze.

Perhaps you want your external solving algorithm to track visited cells inside the maze object itself.

If you do that you are adding new responsibilities to the class, and we don’t want to do that: we like our classes to have a single responsibility.

We can solve the maze without storing state in the Maze class itself.

Perhaps you want to reuse a Maze object by reconfiguring it.

There’s no benefit: just create a new one.

I have no good reason for this class to be mutable, so I will make it immutable.

Initialization

There are various algorithms which can be used to create maze configurations with different visual properties. I want client code to be able to choose the algorithm at run time or to use an algorithm of its own. For this discussion, I have implemented two creation algorithms, which is enough to force the design to support this variability.

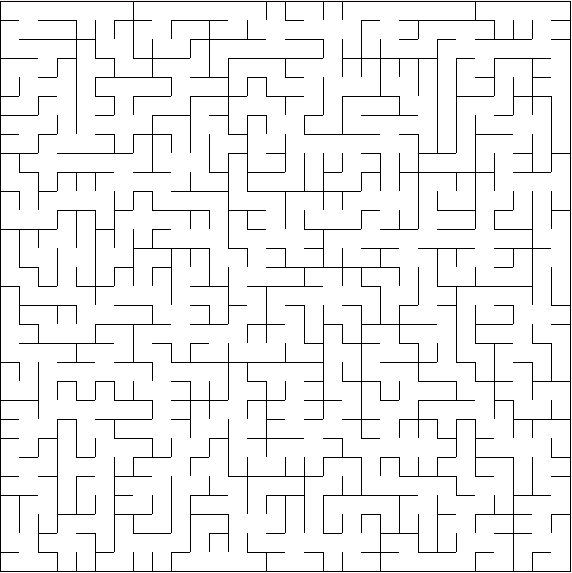

The first algorithm uses a data structure named Disjoint Sets. This algorithm creates mazes with many short dead ends. I discuss the details of the data structure in this article.

Here is an example of a maze created using this algorithm:

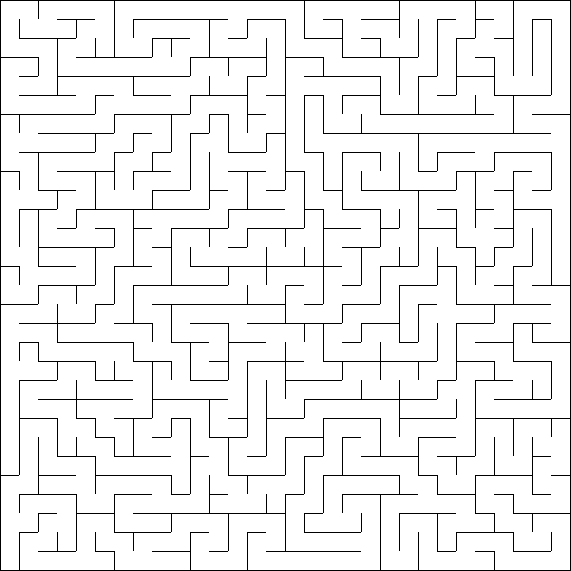

The second algorithm works by randomly wandering around until blocked, and then backtracking. This algorithm creates mazes with fewer, longer dead ends.

Here is an example:

You can imagine other algorithms for creating mazes with different characteristics and different difficulty levels.

Strategies for Initialization

Where will we encapsulate the logic for the various creation algorithms? Let’s examine some possibilities.

Inheritance

Probably the first strategy that comes to mind for many developers will be to create a class hierarchy.

The base class will define a protected data member for the walls and the concrete classes will define an initialization member function to be called in the concrete class constructor to create the wall configuration.

This will work but I don’t like it.

Once created, there is absolutely no difference in the behavior of the concrete classes.

There is no polymorphism at all.

This is using inheritance solely as a means for code reuse.

Additionally, there would be a tight coupling between the internals of the Maze class and the client creation classes.

We are not free to change the internal representation of Maze without breaking client code.

I consider this approach to be bad design.

Nested Builder

With this pattern, you write a nested class or function to create and initialize Maze objects.

You encapsulate the maze creation logic in the builder.

Client code specifies which algorithm to use.

However, this does not meet our requirement of allowing client code to supply its own maze creation algorithms.

This approach does not satisfy the “open/closed” principle.

That is, it is not “open to extension and closed to modification.”

We cannot extend the behavior in our required dimension, allowing client code to add its own initialization logic, with modifying the class itself.

This is not what I want.

Friend Builder

We could write builder functions outside our Maze class and give them friend access to the private walls data member in order to perform the initialization.

But this has the same underlying problem as the Nested Builder approach: it is not “open/closed.”

In order to add a new builder function, you need to modify the Maze class and add the new function as a friend.

Additionally, the friend relationship results in even tighter coupling than the inheritance strategy.

You are exposing the internals of Maze to client code.

Alternatively, you could create an external builder base class and make it the friend.

Then you derive custom builder subclasses from this, delegating the base class as the one to access the Maze internals because it is the one with friend access.

This limits the coupling of the Maze internals to the builder base class.

This is a little better and will work, and it satisfies the “open/closed” principle, but it sure feels awkward to me.

And again we have a class hierarchy with no polymorphic behavior.

I’d like a different approach.

Dependency Injection

With this strategy, we pass an initialization function into the constructor of Maze.

The passed-in function returns a representation of the internal wall layout of the maze.

We could pass the new Maze object to the function as a parameter because it has member functions that are useful to the initialization logic.

This is safe because C++ guarantees the order of member creation.

The basics of the Maze class would look like this:

// A Maze instance is immutable.

class Maze final

{

public:

// Pass in a function used to generate the wall configuration.

template<typename Func>

Maze(std::size_t width, std::size_t height, Func generateWalls) :

mazeWidth(width),

mazeHeight(height),

numCells(width*height),

walls(generateWalls(*this))

{

}

private:

std::size_t mazeWidth;

std::size_t mazeHeight;

std::size_t numCells;

// The walls of the maze are represented as vector of bools, where the

// wall to the east of cell n is wall n, and the wall to the south of

// cell n is wall numCells + n. True means there is a wall between two

// cells. False means there is a passage between two cells.

// Initialized in the ctor.

std::vector<bool> walls;

};

I like this approach because Maze clients can create new algorithms for initializing mazes without any changes to the Maze class.

It satisfies the “open/closed” principle.

The Maze class takes no dependencies on the initialization algorithms.

And there is no coupling to the internals of Maze.

You may be thinking that there is because the initialization function is required to return a std::vector of walls, and this initializes a private data member in the constructor.

True.

However, all I have done is fixed the interface to the initialization function.

We are free to change the internals of Maze if we like; we would just have to convert return value of the initialization function if we did so.

Client code would not have to change.

Note that I have chosen to use a function template to allow passing the initialization function to the constructor. This allows me to pass any callable object that takes the right parameter and returns the right thing. I could have used C function pointer syntax here. Or I could have defined a class interface and required initialization functors to implement it. But by using a function template, I can pass in functions or functors. For now, my initialization algorithms are free functions because that’s the simplest thing that could possible work for this discussion. I guarantee that as this design emerges/evolves, I would change these to functors. But for now, we assume YAGNI.

Refactor

Something bothers me about this approach: it feels weird that we pass “this” to the maze generation algorithms.

They need it because they need the dimensions and they need the utility functions to find the neighboring cell numbers and wall numbers in their algorithms.

Let’s refactor Maze class into two classes: MazeDims to hold the dimensions and utility functions, and a Maze class to hold a MazeDims instance and the walls.

Now maze generation algorithms can take a MazeDims instance to do their work.

To simplify things a little more, let’s pass the output vector<bool> of walls from the maze generation functions to the Maze constructor instead of passing in a function.

This is the full MazeDims class:

class MazeDims final {

public:

enum class Direction {

north,

east,

south,

west

};

MazeDims(std::size_t width, std::size_t height);

// The number of cells in this maze.

std::size_t size() const { return numCells; }

// Returns true if there is a neighbor to the 'direction' of the given cell.

std::size_t hasNeighboringCell(std::size_t cell, Direction direction) const;

// Get the neighbor to the 'direction' of the given cell.

std::size_t neighboringCell(std::size_t cell, Direction direction) const;

// Get the wall to the 'direction' of the given cell.

std::size_t wallIndexInDirection(std::size_t cell, MazeDims::Direction direction) const;

private:

std::size_t mazeWidth;

std::size_t mazeHeight;

std::size_t numCells;

};

The Maze class is reduced to this:

class Maze final

{

public:

Maze(MazeDims mazeDims, std::vector<bool> walls) :

mazeDims(mazeDims),

walls(walls)

{

}

private:

// The width, height, and total number of cells.

MazeDims mazeDims;

// The walls of the maze are represented as vector of bools, where the

// wall to the east of cell n is wall n, and the wall to the south of

// cell n is wall numCells + n. True means there is a wall between two

// cells. False means there is a passage between two cells.

// Initialized in the ctor.

std::vector<bool> walls;

};

Usage of these classes would look like this:

MazeDims mazeDims(11, 15);

Maze maze(mazeDims, wallGeneratorDisjointSets(mazeDims));

You may feel uneasy that the maze generation functions return an std::vector<bool> by value and that it would be expensive to copy.

Good instinct.

But how many times will this initialization function be called?

We don’t know, but probably very few: once per the creation of a new Maze object.

But perhaps you are on the lookout for “premature pessimisations” and would prefer me to create the vector on the heap and return a std::unique_ptr.

Sure, we could.

But return by value here makes the code simpler.

The truth is that the vector will not be copied at all because of Return Value Optimization.

So we’ll keep the return by value and get both the performance and simplicity.

Conclusion

In this exercise, we looked at an immutable class that we want to be configurable by user code. We examined several possible techniques to meet our requirements and ruled them out one by one until we landed on one we liked: dependency injection. Then we refactored to simplify the approach to passing in a fully-built configuration object instead of a service to create one. Remember: you don’t have to invent everything every time you come across a new design problem. Consider existing patterns and see if anything works while maintaining principles of good design.

For the full source, including the code to print the maze to the console, see https://github.com/smeredith/maze/tree/init-immutable.