Using Disjoint-Sets

In a previous article, Data Structure, Disjoint-Sets, I described the data structure known as Disjoint Sets and discussed an implementation. In this article I will discuss using this data structure to construct a maze. Then I will explain how this is similar to using Kruskal’s algorithm to find a minimal spanning tree.

Background

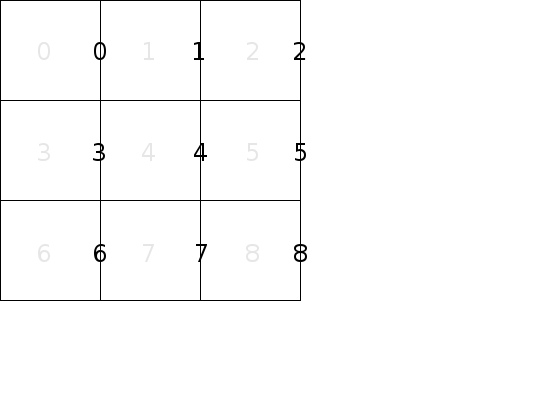

In Choosing a Data Structure I explained that we can represent a maze as a vector of edges where the edges between the cells are labeled as shown below:

For a maze with n cells let’s label the vertical walls of the maze from 0 to n-1, as shown.

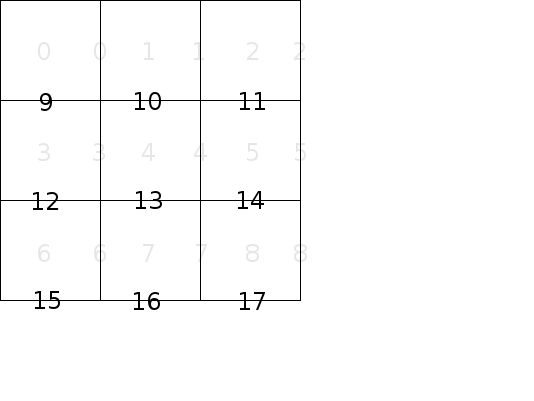

And let’s label the horizontal walls in the same fashion, but starting with n instead of 0, as shown.

To represent the walls, we only need a vector of bits

wallswhere 0 represents a passage between two cells and 1 represents a wall. If two cells are adjacent in the same row, then to find out if there is a wall or a passage between them, index the walls vector with the cell number of the cell with the lower index. For example, to see if there is a passage between cell 1 and cell 2, look at the value of walls[1]. A 1 means there is a wall and a 0 means there is a passage. If two cells are adjacent in the same column, then to find out if there is a wall or passage between them, index the walls vector with n plus the cell number of cell with the lower index. For example, to see if there is a passage between cell 2 and 5, look at the value of walls[n + 2].

Then in A Strategy for Initializing Immutable Objects I explained that our function to generate the walls of a maze should return a vector<bool> to represent the edges as described above.

So all we need to do here is implement that function.

For now we won’t worry about the start and finish cells. Once all the cells are connected we can pick any two cells as start and finish but it’s not relevant to generating the wall configuration.

Implementation

vector<bool> wallGeneratorDisjointSets(MazeDims mazeDims, unsigned int seed)

{

// Vertical walls followed by horizontal walls.

vector<bool> walls(mazeDims.size() * 2, 1);

// Some magic...

return walls;

}

The mazeDims parameter contains the dimensions of the maze and some helper functions.

The seed is used to initialize a random number generator so we can create the same output twice by passing in the same seed.

The idea is to start with a grid of cells with closed walls between each one. Then randomly pick a wall as a candidate to knock down in order to connect two adjacent cells. If there is already a path between those two cells, then we can’t knock down the wall because doing so would result in a cycle. We only allow one path between each cell, so in this case we don’t knock down the wall. If there is not already a path between the two cells, we knock down the wall. We repeat until we have visited every interior wall. Note that outer walls are never knocked down. At the end, there will be exactly one path from every cell to every other cell, and we have the wall configuration for a maze with no cycles or unconnected cells.

We use a Disjoint Sets data structure when considering knocking down a wall.

Conceptually, each set in the data structure represents a path between cells.

We initialized it with one set per node since no node is connected to any other.

As we knock down a wall between cells a and b, we union sets a and b.

So if we want to know if we can knock down a wall between cells c and d, we call findSet(c) and findSet(d).

If they return the same value then the cells are already connected by some path and we can’t knock down the wall between them.

In order to visit walls in random order, we can create a vector of wall numbers and shuffle it.

// Create a vector of wall numbers, then shuffle it so they are in random

// order. We'll use this as the order to visit each wall in "walls".

vector<size_t> wallIndexes = vector<size_t>(mazeDims.size() * 2);

iota(begin(wallIndex), end(wallIndex), 0);

std::mt19937 mt(seed);

shuffle(begin(wallIndexes), end(wallIndexes), mt);

Then we iterate over it and open walls where we can.

DisjointSets sets(mazeDims.size());

// Walk the shuffled list of walls.

for (size_t i = 0; i < wallIndexes.size(); ++i) {

// Assume this is a vertical wall.

MazeDims::Direction direction = MazeDims::Direction::east;

size_t cell = wallIndexes[i];

// Is this actually a horizontal wall?

if (wallIndexes[i] >= mazeDims.size()) {

direction = MazeDims::Direction::south;

cell = wallIndexes[i] - mazeDims.size();

}

if (mazeDims.hasNeighboringCell(cell, direction)) {

if (sets.unionSets(cell, mazeDims.neighboringCell(cell, direction))) {

walls[mazeDims.wallIndexInDirection(cell, direction)] = false;

}

}

}

return walls;

Putting it all together:

vector<bool> wallGeneratorDisjointSets(MazeDims mazeDims, unsigned int seed)

{

// Initially, all maze walls are closed. Each cell will be in a set by

// itself. We'll open walls until every cell is connected to every other by

// some path. Use DisjointSets: cells will be connected if they are in the

// same set.

vector<bool> walls(mazeDims.size() * 2, 1);

// Create a vector of wall numbers, then shuffle it so they are in random

// order. We'll use this as the order to visit each wall in "walls".

vector<size_t> wallIndexes = vector<size_t>(mazeDims.size() * 2);

iota(begin(wallIndex), end(wallIndex), 0);

std::mt19937 mt(seed);

shuffle(begin(wallIndexes), end(wallIndexes), mt);

// Create a collection of sets of cells. Initially, each set contains only

// one cell. We can tell if there is a path to some neighbor if the cell

// and the neighbor are in the same set because when we join a cell to a

// neighbor by opening a wall, we union the sets of the cell and the

// neighbor.

DisjointSets sets(mazeDims.size());

// Walk the shuffled list of walls.

for (size_t i = 0; i < wallIndexes.size(); ++i) {

// Assume this is a vertical wall.

MazeDims::Direction direction = MazeDims::Direction::east;

size_t cell = wallIndexes[i];

// Is this actually a horizontal wall?

if (wallIndexes[i] >= mazeDims.size()) {

direction = MazeDims::Direction::south;

cell = wallIndexes[i] - mazeDims.size();

}

if (mazeDims.hasNeighboringCell(cell, direction)) {

if (sets.unionSets(cell, mazeDims.neighboringCell(cell, direction))) {

walls[mazeDims.wallIndexInDirection(cell, direction)] = false;

}

}

}

return walls;

}

Kruskal’s Algorithm

You can think of the grid of a maze as a graph where each cell is connected to each adjacent cell. You can think of a maze as a spanning tree for that graph. Recall that Kruskal’s algorithm is used to find a minimum spanning tree (MST) for a weighted graph by considering each edge in order of increasing cost and adding edges to the MST using Disjoint Sets if cells are not already connected. If you consider our graph as a weighted graph where the cost of each edge is 1, you could apply Kruskal’s algorithm to find a minimum spanning tree that would be a valid maze. (All spanning trees would be minimum in this case because all weights are the same.) However, the resulting maze would be very uninteresting because each edge is considered in a regular order as cost ties are broken in a deterministic way. If you modified the algorithm to consider each edge in random order instead of by increasing cost, you would end up with an interesting spanning tree. This is exactly what we are doing in the algorithm described above.

Conclusion

The Disjoint Sets data structure can be useful in creating a maze by keeping track of paths between cells as you randomly try to knock down walls. This is not the only way to create a maze, but I have shown that it is an easy way if you choose appropriate data structures. The details are abstracted away and the actual algorithm is only a few lines of code and pretty easy to understand. Additionally, you can frame the solution in terms of Kruskal’s algorithm as another way to understand it.

To see the code in context, see the disjoint-sets-usage branch on GitHub.